Independen -- From one of the rows of aging and fragile tin-roofed houses, an old woman appeared in front of her humble home and trembled as she descended the wooden steps. Her skin was dark and wrinkled, her eyes tired, and there was weariness behind her bursting beautiful smile.

Her name was Yusnani. She lived on the edge of the forest bordering Tanjung Lebar village, Muaro Jambi district, a palm oil transmigration area. Yusnani sometimes collected loose palm leaves or fruits that fell on the ground during harvest time. In a day, she could collect about five kilograms for Rp1,000 (7 cents) a kilo.

Of course, not every day is harvest time. When not collecting fallen fruits or leaves, she went to the forest looking for food, or the river to look for fish.

"When I have no money, I go to the forest, pick rattan shoots and eat them with salt," said Yusnani with clear crystal tears piling up in the corner of her eye on Tuesday (21/7/2020).

She took a deep breath as she imagined the future of her grandson, who would have to live with diminishing customary forests. They would have to survive without land and education, Yusnani said. She feared that they would suffer like her.

Kubu Lalan tribal chief Jupri, Yusnani’s son-in-law, said that the Anak Dalam Tribe (SAD) or Kubu Lalan had difficulty finding food. Apart from the government's ban on clearing the fields, they also feared retribution from the local police and palm oil companies. They also claimed that they were afraid to leave the forest due to the COVID-19 pandemic. They had ceased from hunting activities due to fears of eating contaminated wildlife, as they heard rumors that the virus could be animal-borne. Misfortunes piled up, as wild boars did not sell anymore in the market. Fishing was their only hope.

The Orang Rimba or people of the forest at Bukit Duabelas National Park were facing the same fate. It was also difficult for them to find food during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Warsi Indonesian Conservation Community (KKI Warsi) Director Rudi Syaf said that to avoid COVID-19, the Orang Rimba live by the ‘besesandingon’ tradition. A custom where they self-isolate by going deeper into the forests and avoiding any interaction with strangers.

During this tradition, Orang Rimba divided themselves into three locations, the forests at the Bukit Duabelas National Park (TNBD), palm oil plantations, and industrial plantation forests. They all live dependent on nature—hunting and gathering, with few groups doing simple farming.

When living in the forest, Syaf continued, Orang Rimba fed themselves with gadung (a local yam species) and sweet potatoes. If the latter just needs to be boiled in water, gadung needs to be prepared for three days and then soaked in water for another three days. If done incorrectly, it may not remove the poison altogether or could cause mild intoxication.

Most of Orang Rimba live in palm oil plantations and industrial plantation forest. However, those areas are lacking in food sources. Plus, the game did not sell. They could only rely on the sale of rubber for Rp2,000-Rp3,000 per kilogram.

Rejected by the Local Government

It was a scorching hot afternoon in mid-July. Head of Jambi’s Social and Civil Registration Office, Arief Munandar, rejected the proposal for Orang Rimba to be included in the list of beneficiaries of the local government’s Social Security Service (JPS) scheme.

“It cannot be. We rejected the proposal. We have to properly track them, whether they have [Citizenship Identification Number] or not. There are rules. In distributing JPS, we are monitored by the Inspectorate and law enforcement,” said Munandar.

Indeed, so much help has flowed to the community. There were even overlaps in social aid for the general public—those with a Citizenship Identification Number or NIK were legally entitled to these aids. In contrast to Orang Rimba, who does not have them.

Munandar, on the other hand, also admitted that the local government had erroneously disbursed the assistance to 457 people. This was due to an overlap with the central government causing double recipients. Many who had received them decided to return the aid packages to the local government.

Not only that, the local government only managed to distribute the aids to 27,731 people from the estimated quota of 30,000 people. It is quite a large gap, Munandar added.

Personally, he had thought about splitting the social aid and distributing them to Orang Rimba. Due to the erroneous disbursal and miscalculation, the aid packages—which also contained foodstuff, had piled up in Bulog’s (State Logistics Agency) warehouse for weeks and begun to spoil. Unfortunately, he could not give them away to Orang Rimba unless they have NIK.

“If Orang Rimba in Jambi had NIK, of course, the local government would gladly help them. If not, then why bother. We don’t know where they are, either,” he said, firmly.

No Help Without ID

The State is indeed helping its people during the COVID-19 pandemic. But Jupri and his family have not received any. They also had accepted their fate to be excluded from the government’s aid for living in the forests without any identity.

“Many of us do not have Identity Cards (KTP),” said Jupri.

The Kubu Lalan tribe was spread along the Lalan river, Muaro Badak river, Beruang river, and Tigo Limo river. Most of them do not have ID cards.

"We feel that the government acts as if we never existed. Even when private companies antagonize us, [the government] does nothing. [We don’t expect] they want to help," said Jupri.

Although feeling left out by the government, Jupri still said that he was willing to accept any assistance. He and 300 other families of Suku Anak Dalam, who fall under the auspices of the Kubu Lalan tribe, would be happy to receive them.

Of course, it would help those who are losing their traditional livelihoods and facing food insecurity.

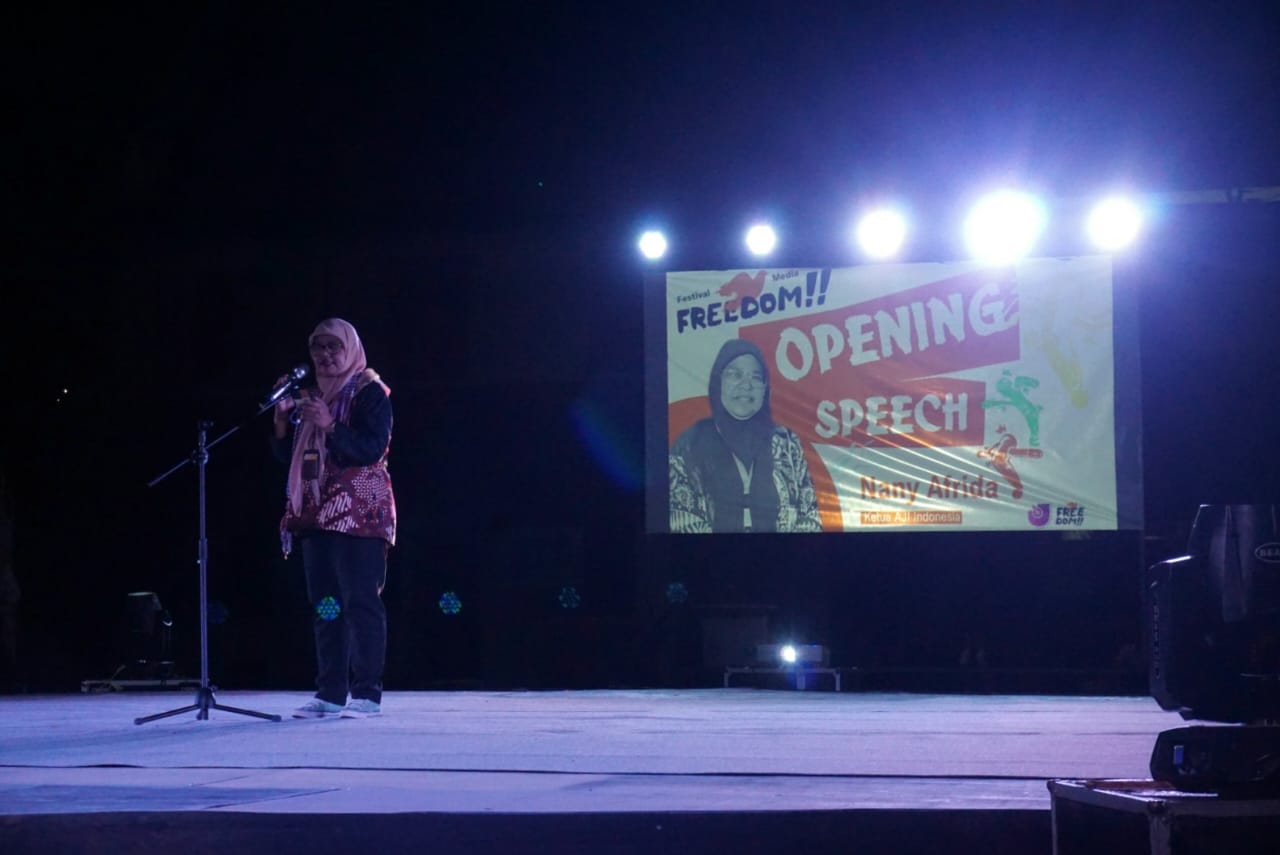

The Ministry of Social Affairs and state-owned postal firm PT Pos Indonesia distributed Covid-19 assistance to thousands of Orang Rimba at the KKI Warsi Jambi field office. (Photo: Suwandi)

Kubu Lalan deputy tribal chief Rusdi, also hoped for government assistance. As a father who had to support nine children, Rusdi found it extremely hard to gather enough food. "We eat sweet potatoes every day. Rice is rare. Because it’s expensive and we don’t have much money," said Rusdi softly.

The inability of Orang Rimba to access government aids had persuaded Rudi Syaf to act. His organization had assisted Orang Rimba for decades, and in this kind of situation, KKI Warsi encouraged Orang Rimba to demand assistance.

However, their request was rejected due to the lack of ID cards. The Government also had not seriously dealt with the legality of Orang Rimba.

Since the country’s independence, most Orang Rimba does not have NIK and ID cards because they are not rooted in any villages. This condition became an obstacle in their administrative records.

Their nomadic lifestyle made it difficult for the government to trace them. Orang Rimba have the melangun tradition or not living permanently in one area after a recent death. Their hunting and gathering way of life also means that they will move around a site to find better food sources.

Their animistic belief also had previously restricted them from acquiring an ID card. Traditionally, Orang Rimba believed in Bedewo. Some would refuse to state other than the Bedewo faith as their religion. But some were forced to pick one of the six officially-recognized religions to get an ID card. This, however, was overturned last year by a Constitutional Court ruling but has yet to take effect nationwide.

“After the seventh religion rule, there is no more [administrational] obstacle for faith groups. But sometimes there are problems in the field. Some officers do not understand the new ruling. So [Orang Rimba] still face discrimination,” Syaf explained.

The remoteness of Orang Rimba’s habitations had made it even more challenging to get access. Especially with the new electronic identification system that requires citizens to submit their biometric data. This could only be done with equipment that is unfortunately difficult to carry around and operate in the jungle.

Waiting for the Government’s Initiative

With various challenges in recording the Orang Rimba population to the national registry, Syaf hoped that the government could develop other initiatives or innovations. First, they are the ones who need to come and visit Orang Rimba to record and retrieve their data.

Then for their registered addresses, the government needs to come with other alternatives. For example, instead of village-based, Syaf suggested using courses of the river as a “home base.” Because Orang Rimba would “stay” around specific watercourses, such as the Makekal, Kedudung Muda, Sako Lado, and Terap rivers.

Syaf also said that for almost four months, the Orang Rimba had difficulties finding food. They are waiting for help to arrive but are instead thwarted by regulations. He feared that if the Government did not act soon, there is likely danger of starvation. Syaf finally took the matter in his hands as he went straight to the Ministry of Social Affairs, submitting thousands of names of Orang Rimba.

Aid must be disbursed immediately for the sake of these people’s s lives. Rules can follow later.

Orang Rimba children studying at a private-owned palm oil plantation during the Covid-19 pandemic with a teacher from KKI Warsi. (Photo: Suwandi)

The answer to Orang Rimba’s plight might come soon. Indigenous Community (KAT) Empowerment Director at the Social Affairs Ministry La Ode Taufik is on the move.

Taufik is following up on the Minister’s directive. Under the order of President Joko Widodo, all Cash Social Assistance (BST) recipients in remote and isolated areas have to be prioritized.

To disburse the BST funds to Orang Rimba, Taufik will ignore his Ministry’s regulations, especially the ones that stipulate that aid recipients should be Indonesian residence registered in the Social Affair Ministry’s Social Welfare Integrated Database (DTKS).

As Orang Rimba have no Citizenship Identification Number (NIK), they are not registered in the DTKS.

However, per President Widodo’s instruction, as a vulnerable group, Orang Rimba was given special leeway such as issuing them with a Temporary ID to be eligible for COVID-19 assistance.

Before KKI Warsi took the initiative to submit Orang Rimba’s data by name by address (BNBA). Taufik claimed that he had sent letters to all Social Affairs Offices at the provincial and district levels to provide the Ministry with data of the local indigenous communities, but received no reply.

“Until the given deadline, no regions have responded to the request. To supply [the ministry] with names. They all said that they were under PSBB [large-scale social restriction] policy. Luckily, Warsi could provide the data so that we can help Orang Rimba,” Taufik said on Tuesday, July 21.

After receiving the data from Warsi, Taufik held a discussion with the Social Affairs Ministry’s Directorate General of Poverty Alleviation (PFM) and Information and Data Center (Pusdatin). They all gave the green light to KKI Warsi’s proposal to provide social assistance to the Anak Dalam tribe: 47 people from the Talang Mamak community, 65 people from Batin Sembilan, 1,229 people from Orang Rimba.

Even though providing assistance to Orang Rimba seemed to be against the rule—giving out social aid to people without NIK, the administration process would resume per usual. For example, Taufik said, before disbursing the assistance, the Social Empowerment Directorate General would send a letter to the Home Affairs Ministry’s Directorate General of Administration. So that the registry of Indigenous Communities (KAT) in Jambi can be facilitated.

Long before the correspondence at the Ministerial level, the KAT Empowerment Directorate had sent a letter to the local civil registration offices with copies sent to the district head. The NIK dan data input process to the Next Generation Social Welfare Information System (SIKS-NG) at the local level. Thus, everything runs in parallel, at the local and the central government level.

After all the administration requirements are fulfilled, the PFM Secretary-General, KAT Empowerment Directorate, Jambi Social Office, Jambi Post Office, and KKI Warsi Jambi coordinated the schedule for distributing the BST to Orang Rimba Jambi groups. It had been agreed that it would be done simultaneously on July 17-18.

Officials from state-owned postal company PT Pos Indonesia distribute the aid based on a BNBA temporary ID. The distribution was done at KKI Warsi’s field office located in the middle of Orang Rimba communities.

“The number of SAD who received BST, as determined by Pusdatin was 1,341 families. Meanwhile, the proposed number was 1,373. So, there is a difference of 32 families, maybe due to data duplicates. The amount of aid disbursed was Rp2.4 billion,” Taufik said.

Each person received Rp1.8 million for three months at a time. After they receive the BST, Taufik hoped that the civil registration documents could be completed this year. So, the task of the regional offices in concern was a critical one.

Money for Food

Sungai Terab community official Ngelembo said that the aid that they received would be used to buy food. He admitted that he had only been eating boiled sweet potatoes during the pandemic. “We will use it to buy rice,” said Ngelembo.

Another Orang Rimba leader, Tumenggung Ngamal from Sako Lado, also said the same thing. He said that since the pandemic, his tribe members had gone deeper into the forest. Living in the wilderness, they had been relying on gadung, benor (another local yam species), and rattan sticks.

Gadung had to be carefully processed before it can be consumed. First, they have to be thinly sliced, soaked in running water, then dried in the sun. Only then can it be cooked. If not, it could have a mild intoxication effect such as headaches, burning sensation in the neck, even loss of consciousness that could last for hours.

Another yam species, benor, had to be dug out, sometimes as deep as two meters to reach it. The tubers were only the size of a human toe. A whole day of digging would probably only fill a small container.

Orang Rimba had also refrained from consuming wildlife to avoid COVID-19 transmission.

The social assistance had very much helped Orang Rimba. Most of them used the money to buy rice.

Saving for Melangun

Ngamal, a member of the Anak Dalam tribe, hoped that after spending the cash assistance on food, they would still have some left to prepare for their melangun tradition. According to him, soon enough, the dry season will come. They have to prepare themselves for food shortages.

During the dry season, fruits are hard to find, a clean water source is scarce, and the fire is a severe threat. That was what Ngamal was afraid of.

Orang Rimba women with their children in a Sudong—a temporary shelter made from tarpaulin roof and wood, during a melangun tradition before the Covid-19 pandemic. (Photo: KKI Warsi documentation)

The remaining funds from the aid can be used to meet their needs during the melangun period, where the tribe would move from one forest to another in search of food and clean water.

“Hopefully, with this assistance, there would be enough to eat, and then for melangun. Because the dry season can cause forest fires,” said Ngamal.

Moreover, KKI Warsi’s Rudi Syaf emphasized that Orang Rimba believed that the dry season is often accompanied by land fires, drought, and food scarcity. That is why they have the melangun tradition during the period. Of course, if they have not used all the money on food, they would use it to deal with forest fires. A prolonged dry season has the potential to subject Orang Rimba to starvation.

In the 2015 fire, 11 Orang Rimba died due to starvation and limited source to clean water. Because of the fire and smog at the time, Orang Rimba had to make their melangun journey as far as the Riau province, traveling hundreds of kilometers.

Syaf hoped that the aid for Orang Rimba will carry on and not only for the three months. Because they are not only fighting against the Coronavirus but also the dry season and forest fires. So instead of just three months, the government should also help them for another three and increase the number of its recipients. He also hoped that the local government could investigate Orang Rimba, who had not received any aids. KKI Warsi will also continue to collect their own data.

Many Orang Rimba Still Being Overlooked

Taufik admitted that there were still many Orang Rimba in Jambi who had been overlooked and had not received any social assistance. According to 2017 data, 6,423 families had been registered. Of this amount, 4,326 families were included in his Ministry’s empowerment program, with the remaining 2,097 families have not.

“Our doors are open. If other parties would like to submit [data] such as Warsi on Orang Rimba with or without NIK and had not received any help. We are going to process them all as long as the BNBA data is complete,” explained Taufik.

He was confident that if the state administration at the regional level were committed to helping Orang Rimba, the process would be more straightforward. Civil registration is a right and had to be fulfilled by the government without exception.

Nevertheless, duplication should be avoided, which means data validity must be upheld. For Orang Rimba, who have received aids from one location, they cannot request another one.

When asked how to guarantee that there would be no double or fake aid recipients in a family, Taufik emphasized that people have to trust each other during the pandemic. When there is someone in need, the government has to work fast.

He said there were still Orang Rimba who had not received any aid because, during data collection, they were already gone for melangun or were not in their group. Help from other parties is needed to anticipate this.

Aid disbursement is not the sole responsibility of the Social Affairs Ministry but rather the regional government as the institution that understood Orang Rimba the best. Fear to disobey rules should not be a reason to ‘remove’ Orang Rimba from the mind.

They are all around us, a vulnerable group who have to face the threat of starvation every day. It is unknown until when Yusnani and her grandson could survive in food scarcity. Surviving without land. Living on rattan shoots and salt. (Suwandi/D02)

This story is made possible with the fellowship on COVID-19 budget transparency with AJI Indonesia and UNESCO